|

Manhattan’s skyscrapers were not only the playground

of superheroes, but giant beehives of business: headquarters

of global corporations, central offices for far-flung plants

and facilities, the focal points of vast commercial energies.

Their lines of communication and authority spread to the ends

of the planet; with utter confidence, their builders considered

them to be the very center of the modern world. No sooner

have we entered their doors, in fact, than we are presented

with symbolic renditions of the earth itself: an enormous

translucent globe in the 1937 lobby of Top of the Town’s

‘Radio Center’ [below], for example, or a futuristic,

two-story-tall chronometer, ringed by a map of the world and

its twenty-four time zones, which sits in the lobby of the

Manhattan headquarters of Janoth Publications, a Time-Life-type

media empire that is the setting of the 1948 film The Big

Clock. As a tour guide explains to his group, the clock’s

complex mechanism does not simply keep time, but actually

regulates activity throughout Janoth’s global domain.

The symbolism is obvious, of course: the towering device

stands for the skyscraper headquarters just as the skyscraper

itself stands for New York — the ultimate ‘big

clock’, constantly pacing the world and tracking its

progress.

Art department sketch from

Top of the Town (1937) |

|

These

symbolic elements also suggest something else: that

the skyscraper holds an entire world within itself —

a complex microcosm of society whose trajectory is drawn

from the shape of the building. In the movie city, we

regularly follow characters on their ‘way up’,

locating in the tower’s upward thrust a model

for other, less visible kinds of movement. Rarely has

this parallel been presented more bluntly (or amusingly)

than in a racy 1933 film called Baby Face: the audience

follows the career of an ambitious newcomer named Lily

Powers (Barbara Stanwyck) by tracking her physical rise

within the offices of the ‘Gotham Trust.’

After Lily gets her first job by seducing the manager

of the personnel department, the saucy strains of ‘St.

Louis Blues’ start to play as the camera pulls

out of the forty-seventh-floor window, rises two stories

to the filing department, and returns inside. Here Lily

meets another supervisor and makes another conquest.

‘St. Louis Blues’ plays again, and again

the camera pulls out the window, rising this time to

the mortgage department, on fifty-one. And so on, through

the accounting and executive offices, until finally

Lily has reached the very top of the building —

the penthouse of the bank’s handsome young chairman,

George Brent. |

However unorthodox her technique, Lily at least works her

way up one step at a time, her gradual ascent precisely calibrated

by the building’s tier upon tier of windows. Yet in

the classic skyscraper era, lavish architectural efforts were

expended precisely to circumvent this sort of plodding, floor-by-floor

rise; instead, the exteriors of skyscrapers sought to suggest

a single, daring leap, an express track to the sky that would

mask the unglamorous stacking of floors within. It is just

this distinction — between interior and exterior, between

a hardworking climb and a swift, dizzying leap — that

frames Joel and Ethan Coen’s parodic exploration of

the classic New York skyscraper, The Hudsucker Proxy (1994).

Constructing the New York skyline for The Hudsucker

Proxy (1994). |

|

It

is 1958, and at the center of a mythic Wall Street skyline

rises the headquarters of Hudsucker Industries, an imposing

depression-era tower whose exterior design — like

those of the actual Manhattan buildings it is based

on — seeks to sweep the eye in an unbroken line

from bottom to top [left].

And it is precisely at those two extremes that the story

begins. At the foot of the building, Norville Barnes

(Tim Robbins), a bumbling but ambitious newcomer from

Muncie, Indiana, is arriving for his first day on the

job, ready and eager to work his way up. At the top,

meanwhile the man who built the building — and

the immense corporation within it — has chosen

that very moment to make a dramatic move in the opposite

direction, leaping out of the forty-fifth-floor boardroom

window and plunging to his death. Cinematically elongated

in time and space, the fall of corporation chairman

Waring Hudsucker (Charles Durning) feels not scary or

tragic but oddly exhilarating, as we sail right alongside

the plummeting figure, the vertical lines of the building’s

sleek exterior racing beneath us like railroad track,

the camera angled, for much of the distance, up the

length of the soaring tower — as if to recall,

even at this most terrible of moments, its original

ascendant promise. |

The Hudsucker Proxy (1994). |

Indeed,

within hours, the hapless Norville is making that very

ascent — at a rate only slightly less impressive

than Hudsucker’s fall — when he is elevated

from a lowly position in the building’s inferno-like

mailroom to its airy executive offices, not through

any hard work or intelligence on his part, but as the

unknowing patsy — or ‘proxy’ —

of a boardroom scheme to depress stock values and buy

up the company at a bargain. That these executive offices,

for all their imposing size and high polish, may have

grown a bit too detached from the world below is powerfully

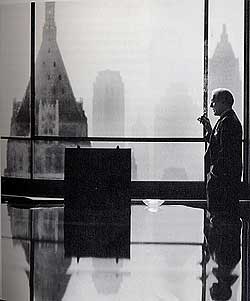

conveyed by a shot of Hudsucker’s successor, Sidney

Mussburger (Paul Newman), silhouetted in the high boardroom

windows. Not only Mussburger — the cynical, grasping

executive who has instigated Norville’s rise —

but Wall Street’s towers themselves are reflected

in the mirror-smooth boardroom table, so as to appear

to float weightlessly, utterly disengaged from everything

else [left]. |

But there is far more to the skyscraper then the airy, detached

realm at its top, as we discover when Norville pulls an idea

out of his pocket — a crude pencil sketch of something

that turns out to be the hula hoop — and, indulged by

Mussburger, is allowed to carry the idea through to execution.

In a succession of rapid shots that, among them, manage to

spoof almost every New York office movie ever made (from The

Apartment to The Crowd to The Big Clock itself), we tour the

divisions that fill the length of the Hudsucker Building:

the design department, the advertising department, the accounting

department — even a proving lab where Norville’s

innocent invention is submitted to explosive testing. But

all of Norville’s good intentions are no match in the

end for Mussburger’s evil designs, and the film’s

climax finds the young man in the sad position of Hudsucker

himself — standing outside the forty-fifth-floor window,

contemplating a fatal plunge. ‘You had a short climb

up, kid,’ Mussburger gloats, ‘but it’s a

long way down.’ For all its layers of irony, The Hudsucker

Proxy ultimately takes us on a surprisingly full and complete

tour of the New York skyscraper, inside and out, revealing

along the way the profound disjunction between the reality

of its interior, whose stratified hierarchy of office floors

might well take a lifetime to surmount, and the seductive

(if potentially treacherous) promise of its exterior —

that the entire length of the building might be negotiated,

one way or the other, in a single, breathtaking leap.

An ambulance races through the city’s streets, rushing

the legendary modern architect Harry Cameron (Henry Hull)

to the hospital. Inside, the great man is flat on his back,

close to death, hardly able to speak — the ideal opportunity,

apparently, for him to deliver a lengthy disquisition on the

buildings he sees through the ambulance window.

‘Skyscrapers,’ he proclaims, as his protégé

Howard Roark (Gary Cooper) draws close, ‘the greatest

structural invention of man! Yet they made them look like

Greek temples, Gothic cathedrals, and mongrels of every ancient

style they could borrow. I told them that the form of a building

was to follow its function! That new materials demand new

forms! That one building can’t borrow pieces of another’s

shape, just as one man can’t borrow another’s

soul!’

Catching sight of a modernist apartment house (actually 240

Central Park South), Cameron brightens briefly. ‘That’s

one of my buildings,’ he says, before relapsing. If

not exactly supernatural, it is indeed a strange world we

have entered — the fervid, peculiarly airless precincts

of the film called The Fountainhead.

Directed by King Vidor and released by Warner’s in 1949,

The Fountainhead closely follows the themes of the best-selling

Ayn Rand novel on which it is based — not surprisingly,

since Rand herself wrote the screenplay. Most everyone knows

the story. Howard Roark, a brilliant modern architect, struggles

to build his bold designs in a compromising world. Rival architect

Peter Keating (Kent Smith) is a timid, conventional designer

who produces neoclassical skyscrapers and at first meets with

great success. But when his career stalls, he implores Roark

to design a housing project called Cortlandt Homes and let

it be submitted under Keating’s name. Roark agrees,

knowing that no project bearing his own signature would be

accepted. When Roark’s radical design is grotesquely

compromised during construction, he dynamites the structures,

reaping widespread public fury. But Roark wins his trial and

is vindicated; by film’s end he is building the tallest

skyscraper in the world.

Intense (and sometimes commercially surreal) subplots of passion

and ambition embroider the film, but at heart Rand sought

to present a parable of ideas, using the battle of architectural

modernism against the older eclectic tradition to exemplify

her philosophical belief in the value of the individual versus

the collective. The year of the film’s release, 1949,

was propitious: the first modern, glass-walled skyscraper,

the United Nations Secretariat building, was just coming out

of the ground, soon to be followed by the first steel-and-glass

commercial office building, Lever House. New York’s

skyline was about to receive its first taste of the new International

Style.

It was a dramatic change. For generations, New York’s

skyscraper architects had pursued their own distinctive course

as they raised up the world’s first and most famous

skyline. For them, the skyscraper’s internal steel frame

was a means rather than an end, something to be freely manipulated

wherever necessary to provide a suitable armature for the

picturesque exterior effects they sought to achieve. They

readily used spires, pinnacles and complex setbacks to shape

their towers into ‘artistic’ compositions, then

clad these structures with ornamented masonry facades that

first drew from classical and Gothic-inspired styles and then,

with the coming of Art Deco in the 1920s, explored their own

decorative motifs.

The design of the new postwar skyscrapers, by contrast, proceeded

from entirely different principles. For modernist architects,

the steel frame beneath the building’s skin was not

just the enabler of its height but the prime generator of

its form. No longer would the steel frame be elaborately shaped

to fit the building’s exterior; now that exterior would

take the form most naturally suggested by the frame itself:

simple, repetitive, boxlike. Nor would buildings be clad in

masonry, or covered with any kind or applied decoration. Now,

sheer flat panels of glass and metal would fill in the frame’s

openings, allowing the internal grid of columns and beams

to become visible on the facade of the building — at

least symbolically. (Fire codes generally disallowed the exposed

use of actual structural elements.) The building’s structure

would become its decoration.

As Cameron’s soliloquy might suggest, The Fountainhead

took sides without apology. In the film, the older eclectic

tradition symbolizes spineless collectivism, while Roark’s

bold modernism embodies Rand’s philosophy of rugged

individualism. We are intended to agree solemnly when Roark

states firmly that ‘a building must be true to its own

idea.’ We are meant to jeer when sinister critic Ellsworth

Toohey (Robert Douglas) attacks Roark’s work at an architects'

meeting by asserting that ‘the conflict of forms is

too great. Can your building stand by the side of his?’

The Fountainhead (1949). |

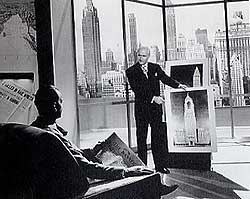

Indeed,

Rand’s insistent message is conveyed not only

by the dialogue, but through the film’s representations

of its competing architects’ work. Under the direction

of Edward Carere, the Warner’s art department

drew up numerous examples of both Roark and Keating’s

‘projects,’ allowing audiences not only

to hear of their relative merits but also actually to

see for themselves. We see a model of the modern slab

Roark has designed for a New York bank, and stand over

the array of widely spaced slabs he has proposed for

Cortlandt Homes [left].

We also review several renderings of Keating’s

office buildings, presented by the cynical Ellsworth

Toohey [below]. |

The art department did its work well: we instantly grasp

the intended distinction between Keating’s pallid, overrefined

classicism, stretched somewhat absurdly across the face of

thirty-story buildings, and the daringly elegant Modernism

of Roark’s designs. Between these loaded examples and

the film’s tendentious dialogue (painting everyone except

Roark as incompetent, weak, or downright evil) it might be

easy to get swept away by Rand’s polemic. But in almost

every scene, another message keeps intruding, utterly contradicting

the rest of the film.

Rand’s novel had been set in New York, but in the film

the city becomes an active, dominating presence through sweeping

skyline views, placed behind almost every one of the movie’s

interiors. These views are made available to the audience

through enormous walls of glass, each one bigger than the

last, each allowing in a different part of the skyline —

Park Row, Fifth Avenue, or, in one case, a starling composite

view that joins midtown and downtown Manhattan. The thinnest

possible metal mullions, often stretching from floor to ceiling,

frame these vivid cityscapes [below]. A moment’s reflection

reveals something odd about these dramatic window-walls. Nearly

all are in buildings that were not designed by Roark —

buildings that, indeed, predate his rise. Isn’t this

strange? Shouldn’t we have merely glimpsed the skyline

through conventional, smallish windows, until we saw it spread

out, spectacularly, in the first of Roark’s daring modern

interiors? Yet every room in the film, the entire ‘world’

in which Roark exists, seems already to have this light and

airy architecture in place.

The Fountainhead (1949). |

In

fact, another priority was at work. The big windows

have one overriding purpose: to make the skyline of

New York a powerful, near-constant force throughout

the film. By allowing the skyline to frame, quite literally,

the film’s debate about architecture, the filmmakers

were likely answering a concern voiced aloud in the

movie itself when — in response to the notion

that a Roark project might make a good subject for a

tabloid exposé — a harried city desk editor

wails ‘Oh, who cares about a building?’

Warner’s executives may well have had a similar

fear, that the popular audience would not easily connect

with the film’s ‘highbrow’ debate

about architectural styles: Hollywood movies, after

all, are hardly known for drawing their storylines from

obscure aesthetic controversies. |

If architecture was an esoteric topic, however, the New York

skyline was not. Film audiences everywhere knew it, connected

with it — in no small part, of course, thanks to the

movies themselves. So the presence of the skyline in almost

every frame of The Fountainhead was likely prompted by a similar

connection. ‘Pay attention to this debate about architecture,’

the producers were saying in effect to the audience, ‘because

architecture shapes this skyline that you know so well.’

The skyline became the popular passport into what might be

considered an elitist subject.

But there was a price. The sustained prominence of the skyline,

even in the background, worked to subtly subvert the film’s

intended message. Seen as renderings, one by one, Keating’s

classical office towers do seem insipid and perhaps ridiculous

— the ‘big marble bromides’ that one character

calls them. But that skyline out there, made up of buildings

not at all dissimilar to Keating’s, is something else

entirely. It is dramatic, exciting, bursting with energy —

as no one knew better, obviously, than the filmmakers themselves,

who used it shamelessly to capture and hold the public’s

attention. Roark’s modern skyscrapers, meanwhile, undergo

a transformation just as profound, but in reverse: while his

solitary Manhattan bank tower is convincingly sleek and daring,

his plan for the multibuilding Cortlandt Homes appears to

be the drab, single-minded work of a dull student. The scheme

evinces no notion of a ‘city’ beyond the repetitive

placement of identical buildings; it offers no means of varying

the mix nor composing the group to achieve any sense of vitality

or energy.

We are left with a paradox that has troubled observers of

the city for more than half a century — and that still

remains largely unanswered. Even the most elegant or dynamic

of modern skyscrapers have tended to remain wrapped in a kind

of urban solipsism, focused on their own ‘integrity’

at the expense of all else. Obsessed with being ‘true

to their own idea,’ they speak most significantly to

those relatively few observers — critics and historians

of architecture, as well as architects themselves —

who are inclined to view each skyscraper as an individual

work of art, and who, furthermore, consider the skyscraper’s

status as ‘the greatest invention of man’ to be

its extremely important aesthetic fact as well. Yet as The

Fountainhead itself implicitly admits, most everybody else

sees things quite differently. The film’s high-flown

arguments for the skyscraper as a singular work of art, an

object whose form is determined first and last by its structure,

were entirely undercut by the producers’ shrewd and

knowing recognition that, in fact, the public was devoted

to a skyline built on entirely contrary principles, a skyline

in which any single structure was but one piece of something

larger, its shape to be freely manipulated to contribute,

scenographically, to the overall ensemble. As The Fountainhead

made clear almost despite itself — what was perhaps

banal or absurd in the single electric building could somehow

become dramatic or alive when joined with its neighbours.

Before our eyes, The Fountainhead reasserts the powerful transformation

that takes place when the frame of architectural reference

shifts from the unit to the group, from the one to the many

— a strange and potent alchemy that has proved the puzzlement,

and the bane, of the modern city.

|